Half of Severe Hemophilia A Cases Have No Family History, Delaying Diagnosis but Not Raising Inhibitor Risk

According to a new study in Haemophilia, up to 60% of patients with severe HA have no known family history, making early diagnosis more difficult.

Over half of patients with severe

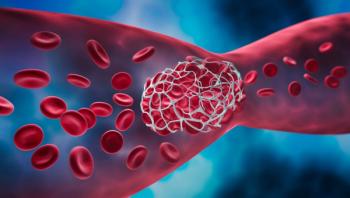

HA is an inherited bleeding disorder caused by mutations in the F8 gene and typically follows an X-linked recessive pattern, meaning it often runs in families.

The

Among U.S. births, HA occurs in approximately 1 in every 5,600 male births, while hemophilia B is less common, affecting about 1 in every 19,300 male births.

This new study supports the unfortunate finding that up to 60% of patients with severe HA have no known family history, making early diagnosis more difficult.

In these "sporadic" cases, diagnosis often occurs only after a child experiences significant bleeding, which can delay the start of treatment and limit opportunities for early preventive care.

This delay is important because the development of inhibitors remains a major complication, according to study authors.

These treatment-blocking antibodies form in about 20% to 35% of patients with severe HA, especially during the first 50 days of exposure to factor VIII replacement therapy.

While newer treatments such as Hemlibra (emicizumab) offer non-replacement options to reduce bleeding risk, the risk of inhibitor development still exists when traditional factor therapy is used.

Both genetic and environmental factors influence inhibitor risk, including certain gene variants, treatment intensity and age at first treatment, authors share.

This study, using data from the PedNet-RODIN international birth cohort, aimed to confirm whether a lack of family history leads to delayed diagnosis, treatment—and whether that delay affects bleeding patterns, genetic variant profiles and the risk of developing inhibitors in children with severe HA.

Included in the study are children with severe HA, born between 2000 and 2022, who were treated at one of 29 centers across Europe, Israel and Canada and enrolled in the PedNet registry.

Only patients with clear family history data were included.

Researchers tracked each patient until they developed inhibitors or received 50 exposure days (EDs) of clotting factor.

Data collected included patient age at diagnosis, bleeding and treatment history, and genetic mutations. Inhibitor development was monitored with regular testing.

All treatment types—except non-replacement therapies—were recorded. Patients’ family history was classified as positive or negative, and outcomes were compared between these groups.

Statistical tests were used to analyze bleeding patterns, treatment timing, gene variants and inhibitor rates.

It was found that in 1,208 patients with severe HA, 54.1% had no known family history of the condition at the time of diagnosis, while 45.9% did.

Patients with a family history were diagnosed about eight months earlier on average and started treatment sooner than those without.

Although all patients received treatment within a year, those with a family history were more likely to begin with preventative (prophylactic) care rather than treating active bleeding.

However, bleeding was more likely the reason for first treatment in patients without a family history, who also experienced more intense treatment episodes.

While patients with a family history began prophylaxis slightly earlier, the timing was not significantly different between groups.

There were no differences in the type or dosing of clotting factor used.

Out of 823 patients without inhibitors, those with a family history experienced their first bleeds earlier, but the overall number of bleeds over time was similar between groups.

Inhibitors developed in 30% of patients, regardless of family history, though they appeared at a younger age in those with a family history.

A genetic analysis showed a similar result of risk variants for inhibitor development in both groups, with no significant differences.

Out of the entirety of data collected, a key strength of the study includes its large, unselected cohort of over 1,200 patients with severe HA and its detailed comparison of patients with and without a known family history.

One limitation is that the data are from a historical cohort, so treatment patterns may differ today with newer therapies such as emicizumab, which allow earlier and less invasive prophylaxis.

Also, the study did not explore in depth how non-replacement therapies might influence inhibitor risk, especially in newly diagnosed or previously untreated patients.

Study authors suggest that earlier genetic screening, particularly in families with unknown hemophilia history, could help identify carriers sooner and improve outcomes.

They also stress on the importance of early treatment to prevent bleeding complications, particularly peak treatments during initial emergency care.

Newsletter

Get the latest industry news, event updates, and more from Managed healthcare Executive.