Antifibrotic therapy equally effective in familial and sporadic IPF

Key Takeaways

- Antifibrotic therapy shows similar efficacy in familial and sporadic IPF, with no significant differences in survival or acute exacerbations.

- Familial IPF patients tend to be younger and more likely female, but have similar disease burden at treatment initiation.

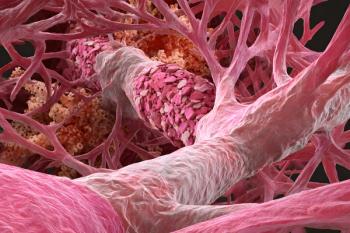

Because familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is associated with earlier onset and worse outcomes, there are questions about the effectiveness of the antifibrotics as a treatment.

A new study by researchers in the Department of Internal Medicine at Hamamatsu University School of Medicine in Japan suggests that patients with familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and those with the sporadic form of the disease benefit equally from antifibrotic therapy, with no meaningful differences in survival, acute exacerbations or treatment discontinuation.

Led by Keisuke Morikawa, M.D., and colleagues, the

Antifibrotic agents, such as Esbriet (pirfenidone) and (Ofev) nintedanib are widely used to slow disease progression in IPF and other forms of progressive pulmonary fibrosis and while randomized trials have demonstrated benefit in heterogeneous IPF populations, patients with known familial disease have been underrepresented, leaving uncertainty about treatment outcomes in this group.

“Familial disease has historically been associated with earlier onset and worse outcomes, raising questions about whether current antifibrotic therapies are equally effective in this population,” Morikawa said.

To address this gap, the researchers analyzed real-world outcomes among 280 patients with IPF who received antifibrotic therapy across multiple centers in Japan. The cohort included 45 patients who met criteria for familial IPF. The other patients were all classified as having sporadic disease.

For the study, patients were followed for treatment discontinuation, acute exacerbations and overall survival. Discontinuation included cessation of therapy for any reason, including adverse drug reactions, disease progression or patient preference. Acute exacerbation was defined using established clinical criteria, and survival analyses were adjusted for disease severity using the gender-age-physiology index.

The data showed ome expected differences between the two groups, according to the researchers, as patients with familial IPF were younger at the time of antifibrotic initiation and more likely to be women compared with those with sporadic disease. What’s more, smoking history, lung function measures and body mass index were otherwise similar, suggesting comparable disease burden at treatment initiation.

Across both exploratory and validation cohorts, antifibrotic therapy discontinuation occurred in 102 patients, representing more than one-third of the total study population.

“Statistical analyses showed no significant difference in cumulative discontinuation rates between patients with familial IPF and those with sporadic disease,” the researchers wrote. “Importantly, the reasons for discontinuation, including adverse drug reactions, were similar between groups, suggesting comparable tolerability.”

Rates of acute exacerbation also did not differ significantly by familial status. Acute exacerbations are a major driver of morbidity and mortality in IPF, and their comparable incidence supports the use of antifibrotic therapy regardless of genetic background.

Findings of survival outcomes saw the same pattern. After adjusting for gender-age-physiology index, familial IPF was not associated with an increased risk of death compared with sporadic disease. The data suggest that once antifibrotic therapy is initiated, disease trajectory may be influenced more by baseline severity than by familial predisposition.

The findings, the authors wrote, have practical implications for clinicians managing patients with a known family history of pulmonary fibrosis.

“While genetic predisposition remains important for diagnosis, counseling and potential screening of relatives, the results indicate that standard antifibrotic treatment strategies remain appropriate for these patients,” they wrote.

Furthermore, the authors note that familial disease alone should not be viewed as a marker of poorer response to therapy.

The researchers caution that the study has limitations inherent to its retrospective design. Treatment decisions were made at the discretion of treating physicians, and unmeasured factors such as environmental exposures or genetic subtypes could have influenced outcomes. In addition, all patients were treated at specialized centers, which may limit generalizability to broader clinical settings.

Even so, the study provides robust real-world evidence comparing antifibrotic outcomes in familial and sporadic IPF. As genetic testing becomes more integrated into interstitial lung disease care, these findings support continued use of antifibrotic therapy across IPF subtypes while reinforcing the need for future prospective studies examining genotype-specific treatment response.

Newsletter

Get the latest industry news, event updates, and more from Managed healthcare Executive.